In 2002 an estimated 98,987 deaths in U.S. hospitals were associated with healthcare associated infections (HAI), according to a study by the CDC. At that time, when a patient acquired an infection 48 hours after being admitted to a hospital, it was called a nosocomial infection. According to researchers, there was nothing particularly unusual about the death toll that year, instead suggesting that it was difficult to attribute mortality based on patient records.

Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria is nothing new. The concern dates back more than 50 years when bacterial resistance started to appear in cases of Staph aureus infections in the 1950s. Methicillin was introduced in 1960, and one year later, methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (MRSA) emerged.

Related Content: Building a Culture of Infection Prevention

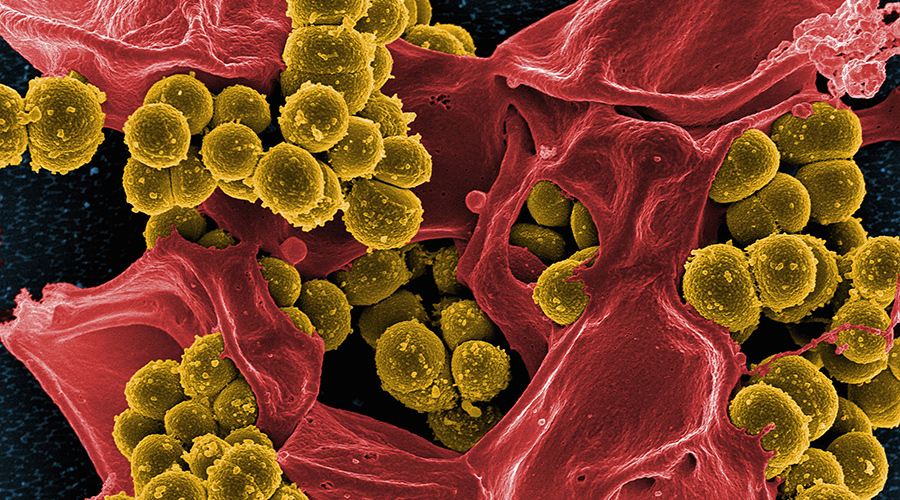

Since then, different strains of superbugs have emerged. MRSA, the most widely known and one of the original superbugs, has been followed by a slew of other superbugs that all have one thing in common: resistance to antibiotics. A group of six hospital-borne pathogens known as ESKAPE (Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and Enterobacter) were present in hospitals starting 61 years ago. Now Candida auris with a mortality rate of 40-60 percent, is an emerging threat in hospitals and long-term care facilities.

The CDC estimates that about 23,000 people die each year from 17 types of antimicrobial-resistant infections and that an additional 15,000 die from Clostridium difficile, a pathogen linked to long-term antibiotic use.

Disinfecting surfaces of superbug pathogens is significantly more difficult than it is for typical germs, and it is a major challenge in long-term care and other healthcare facilities. While effective disinfectant products and processes exist, their successful application depends heavily on consistent and thorough cleaning techniques and the selection of the most effective agents for the specific pathogen.

The main factor contributing to the difficulty is biofilm formation. Superbugs often form a protective matrix called biofilm, which can make them highly resistant to common disinfectants. Research has found that most hospital-grade disinfectants, including concentrated bleach, were ineffective at damaging the spores of certain superbugs within biofilms.

Simple cleaning of the environmental surfaces might be one of the key defenses when Darwinian evolution finally terminates the antimicrobial era. Hospitals should lead the way by studying clean and measuring the results that would offer some semblance of safety to patients.

J. Darrel Hicks, BA, MESRE, CHESP, Certificate of Mastery in Infection Prevention, is the past president of the Healthcare Surfaces Institute. Hicks is nationally recognized as a subject matter expert in infection prevention and control as it relates to cleaning. He is the owner and principal of Safe, Clean and Disinfected. His enterprise specializes in B2B consulting, webinar presentations, seminars and facility consulting services related to cleaning and disinfection. He can be reached at darrel@darrelhicks.com, or learn more at www.darrelhicks.com.

Healthcare and Resilience: A Pledge for Change

Healthcare and Resilience: A Pledge for Change Texas Health Resources Announces New Hospital for North McKinney

Texas Health Resources Announces New Hospital for North McKinney Cedar Point Health Falls Victim to Data Breach

Cedar Point Health Falls Victim to Data Breach Fire Protection in Healthcare: Why Active and Passive Systems Must Work as One

Fire Protection in Healthcare: Why Active and Passive Systems Must Work as One Cleveland Clinic Hits Key Milestones for Palm Beach County Expansion

Cleveland Clinic Hits Key Milestones for Palm Beach County Expansion