During the late 1980s and early 1990s, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis B (HBV) and Hepatitis C emerged and all remain a global concern. These bloodborne pathogens are life threatening and are not respectful of age, race, gender or sexual orientation.

The term infection control is usually assigned to a person or department in a hospital or long-term care facility. The goal of infection control is to halt or limit the spread of bacteria, microorganisms and fungi. Environmental Protection Agency -registered disinfectants are the main weapon in the battle to control the transmission of hospital-acquired infections that live and multiply on surfaces in the patient’s environment.

In 1989, the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) said, “Blood is the single most important source of HIV and HBV in the workplace setting.” Every occupation, but especially healthcare workers, risk exposure from contact with another person’s blood.

There are three routes of entry for bloodborne pathogens: through breaks in the skin or open wounds and sores; injection with a needle or other instruments that can cut or break the skin; and contact with mucous membranes (i.e., skin, eyes, nose, or mouth).

The degree of risk to a worker, patient, resident or the public depends on the degree of exposure. Cokendolfer and Haukos state in The Practical Application of Disinfection and Sterilization in Health Care Facilities, 1996:

“The following four factors are critical in assessing the potential risk of exposure:

Enough organisms present to cause disease. Each illness requires a certain number of infectious organisms to be present to cause disease. If only a small number of organisms are successfully transmitted, the host might not acquire the disease.

Virulence of the disease-producing organism. Virulence is the potential or power of the organism to cause disease. The pathogen first must overcome environmental exposure and the body’s defenses. In most cases, the organism must be viable outside the body. For example, HBV has been shown to remain viable either in blood or bodily wastes containing blood, plasma, or serum and potentially infectious even after a week on a surface (Bond and others, 1981). On the other hand, HIV has been shown to be susceptible to environmental influences and rarely survives outside of the human body. The risk of transmission of HIV is much lower than that of HBV. Less than 1 percent of occupational parenteral exposures to HIV-contaminated blood or body fluids result in HIV infection, while similar exposures to HBV result in a 26 percent infection rate (Sattar and Springthorpe, 1991).

Route of entry. For the pathogen to successfully transmit disease, it must be introduced into the host through the appropriate route of entry. Tuberculosis is most transmitted via inhalation of airborne droplets, and thus, inhalation is the most successful route of exposure for this bacterium.

Host resistance. Host resistance is the ability of the host to fight and prevent infection. Infection occurs as the result of an interruption in the body’s normal defense mechanisms, which allow organisms to enter the body. Typically, the healthier the individual, the less likely he or she will become ill.”

When deciding where to disinfect, environmental services managers must consider guidelines established by OSHA, the CDC and state and local regulatory agencies. The answer to that question lies in common sense and regulations. Common sense dictates that high-touch items are routinely disinfected.

On the other hand, the CDC states that universal precautions be used. Universal precautions are based on the premise that there is a potential for infection with every drop of blood and certain other body fluids — e.g., semen, vaginal secretions and cerebrospinal, synovial, pleural, peritoneal, pericardial, and amniotic fluids.

J. Darrel Hicks, BA, MESRE, CHESP, Certificate of Mastery in Infection Prevention, is the past president of the Healthcare Surfaces Institute. Hicks is nationally recognized as a subject matter expert in infection prevention and control as it relates to cleaning. He is the owner and principal of Safe, Clean and Disinfected. His enterprise specializes in B2B consulting, webinar presentations, seminars and facility consulting services related to cleaning and disinfection. He can be reached at darrel@darrelhicks.com, or learn more at www.darrelhicks.com.

Reframing the Construction Manager as a Community Manager

Reframing the Construction Manager as a Community Manager Health First Celebrates 'Topping Off' Ceremony for New Cape Canaveral Hospital Campus

Health First Celebrates 'Topping Off' Ceremony for New Cape Canaveral Hospital Campus The University of Hawai'i Cancer Center Caught Up in Cyberattack

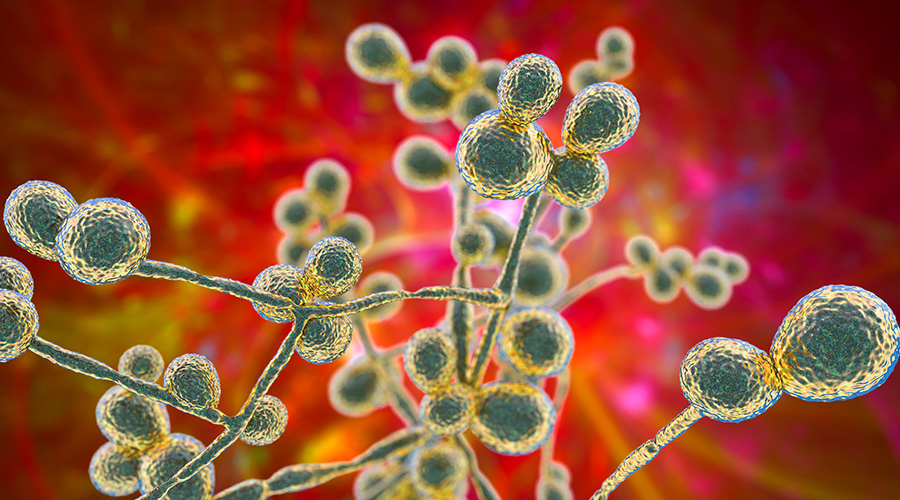

The University of Hawai'i Cancer Center Caught Up in Cyberattack Mature Dry Surface Biofilm Presents a Problem for Candida Auris

Mature Dry Surface Biofilm Presents a Problem for Candida Auris Sutter Health's Arden Care Center Officially Opens

Sutter Health's Arden Care Center Officially Opens